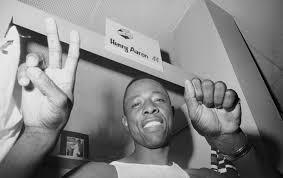

He Had a Hammer: Henry Aaron Presente

As an icon passes away at 86, let’s remember him for more than home runs. Let’s remember the fact that he wore his scars borne of racism with defiance and pride.

When you write for a living, you invariably pen obituaries in advance so they are ready to be published as soon as the death knell of the famous is sounded. I could never do that with Henry “Hank” Aaron. Even at 86, he seemed so precious that I was in no position to even imagine a world without him. He seemed too important to die, like a monument that people would form a human chain to protect against the hordes determined to tear him down. Aaron was living testimony not only to greatness with a bat but to this country’s racism. His willingness to testify to this reality made him the foe of the darkest corners of this country, from chat rooms to the White House.

What we have lost in Aaron is more than just an all-time baseball player (he is among the best to ever take the field, with a record 25 All-Star selections, more RBIs than any player who ever lived, and a decades-long reign as Home Run King with 755 dingers, even though he never hit more than 47 in a season). We have lost one of our last living links to the Negro Leagues, where Aaron played for several months with the Indianapolis Clowns. We have lost someone who, even though he played much of his career in Atlanta, was a fierce foe of Jim Crow—and then the New Jim Crow, with its savage inequities in the criminal justice system. As he once said, with his deep and sincere humility, “Am I a hero? I suppose I am, to some people. If I am, I hope it’s not only for my home runs.… I hope it’s also for my beliefs, my stands, my opinions. Still, I’m not at ease being a hero.”

We also lost someone who could attest like no one else to the racism that runs deep in the marrow of this country and the limits of sports heroism as a vehicle to transcend that racism for the Black athlete. It was Aaron who was mercilessly threatened with murder as he chased down Babe Ruth’s record of 714 home runs in 1973. Aaron came up just shy, breaking the record in April of 1974. But that meant he received a tonnage of letters that winter—the most anyone in the United States not named Richard Nixon had ever received—that alternately pledged support or promised death for him and his family. The latter were the letters Aaron never threw away. These threats were so vicious that Aaron and his family needed bodyguards—even his daughter, who was away from home at the time. The threats were so vicious that The Atlanta Journal-Constitution pre-wrote an obituary to have on file in case of his assassination. Remember, this was just five years after the killings of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, so the idea that greatness could be snuffed out at a moment’s notice was not far from the American imagination.

When Aaron was making his iconic home run trot in 1974 after hitting number 715 off of Al Downing, two young white hippies ran out of the stands to shake his hand, smiles on their faces. They had no idea that Aaron’s bodyguard, Calvin Wardlaw, had his hand on his gun ready to end their lives if the situation went sideways. This should have been his singular moment of unvarnished joy—instead, it was nearly a crime scene. As Aaron said, “It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about. My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

Later in life, Aaron was able to heal, but he was never shy about showing his scars. He was a superstar of uncommon decency who had lived through segregation and Jim Crow only to come out on the other side ready to lend his name and fame to keep the struggle alive. In 2018, he was asked whether he would visit Donald Trump’s White House and he answered simply, “There is no one there that I want to see.” This was a special man, and it is an indelible mark of shame on this country that he wasn’t treasured through every phase of his life. The most we can hope for now is to hold his memory high and stand on his shoulders for the battles to come. As Aaron said, “My motto was always to keep swinging. Whether I was in a slump or feeling badly or having trouble off the field, the only thing to do was keep swinging.” Damn right.

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!