Jim Brown’s War Within Himself

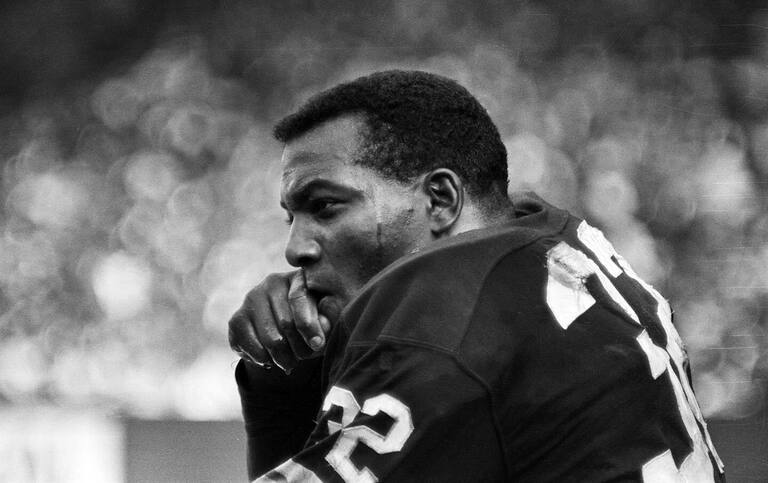

Jim Brown. (Bettman / Getty)

The passing of the football great is an opportunity to speak about his tangled legacy.

The alert came across my phone from The New York Times: “Jim Brown died at 87. An acclaimed football player, actor, and civil rights activist, he was accused of domestic violence.” It was a lot to take in. I had spent four years writing a book about his life called Jim Brown: Last Man Standing, from which much of this article stems. As part of that project, I stayed at Brown’s house in the West Hollywood Hills for a week, and despite his age and health, it was difficult to imagine him ever dying. The Times alert showcased a fool’s errand in its attempt to drill his life down to 20 words. Here he is being called a civil rights activist when he opposed much of the politics and many of the methods and tactics of the civil rights movement. He derided civil rights marches as “parades” in the 1950s and then again in 2016. That was when he engaged in an ugly, public feud with Representative John Lewis, whom Brown condemned for questioning Trump’s legitimacy. By that time, Brown supported Trump, a position that I argued made sense given his politics, which were both consistent and complicated. Brown supported Richard Nixon in 1968 and spoke at Huey Newton’s funeral in 1989. What is not complicated is his treatment of women. Again, to break that down to only “was accused of domestic violence” does both the history and the survivors an injustice. Brown’s life calls for more than genuflection or dismissal; it demands study.

Football is the closest thing we have in this country to a national religion, albeit a religion built on a foundation of crippled apostles and disposable martyrs. In this brutal church, Jim Brown was the closest thing to a warrior-saint. Brown was both statistically and according to awed eyewitnesses perhaps the greatest football player to ever take the field. At six-foot-three and 230 pounds, running a sub-four-and-a-half-second 40-yard dash, he was like a 21st-century Terminator sent back in time to destroy 1950s and ’60s linebackers. In the gospel of football, defensive demons like Dick Butkus or Lawrence Taylor have carried some of that fearful mystique: transforming their opponents into quivering balls of gelatin. But on offense, the all-time great skill players have inspired adulation but never physical fear. On that side of the line of scrimmage, the list of true intimidators began and ended with Jim Brown.

The statistics that define his time in football are still without equal. Brown played nine years and finished with eight rushing titles, a level of consistent greatness no one has come close to matching. He was the only player to average 100 yards rushing per game over an entire career, getting five yards with every carry. Then there was the most impressive number of all: zero. That was the number of games Brown missed over his nine years in the league. It would be an achievement for a place kicker. But it was especially remarkable given the ungodly workload Brown maintained and the constant punishment he took, touching the ball for roughly 60 percent of all of the Cleveland Browns’ offensive plays.

But Brown was also more than an athlete even when he was an athlete. He was in many respects the first modern superstar, again as if arriving from the future. In an era before strong sports unions, he organized his locker room to stand up to management on issues great and small, never giving an inch and earning a derisive nickname from team executives, “the locker room lawyer.” Fifteen years years before Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists for Black athletes at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Brown was the one who refused to be treated as a second-class citizen because of the color of his skin. In the time before Muhammad Ali “shook up the world” by joining the Nation of Islam and refusing to fight in the Vietnam War, it was Brown whom Ali turned to for advice and support.

Brown was the first player to use an agent. He was the first superstar to successfully demand that a coach be fired and that released teammates be immediately un-released. He was the first athlete to ever willingly quit his sport in his prime, because his “manhood” was more important to him than enduring the disrespect of management. He was the first Black athlete to be bigger than the league itself. When players like LeBron James have leveraged their own stardom to assert their will on the direction of their teams and their leagues, it all traces back to Brown.

If that were where Brown’s story ended, it would fill volumes. But his football life was just the opening salvo in a much more sprawling epic. Brown parlayed his athletic fame into Hollywood stardom, where it was thought he could become “the Black John Wayne.” When this path was stymied by the racialized rules of Hollywood, he became the first Black actor to try to rewrite the script by launching his own mainstream, big-time production company to make “Black films for a mass audience,” along with his partner the comedian Richard Pryor, before they had a falling out for the ages. He was an outspoken Black Power icon in the 1960s and spearheaded a network of Black economic unions to build independent hamlets of financial strength in the Black community.

Brown has had his supporters and detractors. But the common thread that one hears from everyone who has had dealings with him—dealings good, bad, and ugly—is that “Jim Brown is above all else, a man.”

This word “man” might as well have been a birthmark affixed to Brown when he arrived in the world on February 17, 1936. His nickname as a small child was “Man,” and the word “manhood” is the political current that pulses throughout his life

Kevin Blackistone wrote in The Washington Post in 2017 that “Brown, maybe more so than any other black athlete the past 50 years, came to be seen as sort of an emperor of black masculinity and of black power.” Brown’s assertion of his own unassailable masculinity conjures another legend who was a friend and contemporary, Malcolm X. In his eulogy for the icon of Black empowerment, the actor Ossie Davis said, “Malcolm was our manhood.” Davis, in his stentorian voice, was arguing that Malcolm embodied Black masculinity, valor, and heroism in a society dedicated to treating and labeling Black men as “boys.” Brown quite self-consciously cut himself from that cloth.

Brown asserted his fierce sense of manhood as a principle of emancipation. On the most hyper-masculine cultural canvases of the United States—NFL football, the Black Power movement, Hollywood’s Blaxploitation era, the gang wars both inside and outside prison walls—Brown made his mark. In the most toxic expression of how our society defines “what makes a man”—the assertion of domination over women—he has left a very different kind of legacy. This history of accusations of violence against women levied against him have scarred his legacy. When pressed about all of these incidents, Brown only said, “There’s been lies written about me, there’s been some truth, too. I’m no angel, but what I do, I tell the truth about.”

It was not merely that Brown did not take the accusations of violence against women seriously. No one in power really did. Art Modell, the former owner of the Cleveland Browns, said in one interview, wise-guy smile in place, that Brown “got into trouble because of, shall we say, a rough social encounter with a gal, or two, or three.”

The cases against Brown are extensive. He often said that he has “never been convicted of violence against women,” which is true. But almost all the cases tended to follow a script that was far too common at the time: Women, exclusively women of color, making heinous accusations against Brown, then facing all sorts of harassment and disbelief, and dropping the charges. Brown also shook his head when I asked him about this history, and he only said, “Violence against women… shit,” as if he could not believe this still followed him so late in life. Yet the cases span the years from 1965 to 1999. It’s a remarkable stretch that cannot be written off as just an endless series of law-and-order conspiracies, coincidences, or bad luck. If we are going to tell Brown’s story, it is irresponsible to not say the names of Brenda Ayres, Eva Bohn-Chin, Debra Clark, and others.

As the years passed and at least a minority of people started taking these allegations seriously, they prevented him from achieving the kind of mainstream adulation bestowed upon contemporaries like Ali and Bill Russell. Barack Obama, who as president took a particular joy in interacting with Black sports heroes of yesteryear, never invited Brown to the White House, which stung. Donald Trump, however, rolled out the red carpet. In December 2016, the president-elect sat down with Brown and former NFL player Ray Lewis. Brown left the meeting saying, “I fell in love with [Trump] because he really talks about helping Black people.”

If we understand Jim Brown’s actual political beliefs over the last 50 years—and not the beliefs we projected onto him—his meeting with Trump should have surprised no one. His history shows that in addition to being a great football player, legendary tough guy, and anti-racist icon, Brown was always a mess of contradictions. He’s the anti-racist who condemned Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of the civil rights movement as a waste of time. He’s the NFL rebel who has long been at odds with the NFL Players Association. He was almost alone in fighting for the life of Crip gang founder, multiple-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee, and author Stan Tookie Williams until Tookie’s last day on death row. He also stood with Donald Trump.

Meeting Jim Brown in the flesh in 2014, even at his advanced age, almost answered the question for me as to how he could be widely revered despite his history and politics. He projected a sense of strength that made you want—even with all evidence to the contrary—to be lined up on his side. He walked with a cane as tall and thick as a baby oak. It was a chunk of wood designed to hold up a very specific body; a body that, even with age and a pronounced limp, was striking. He was built like a series of imperfect, craggy cubes, no longer possessing the 47-inch chest and 32-inch waist that made him a Hollywood sex symbol but still looking like he could move a mountain. Yes, he needed that cane to walk. He could not turn his neck. His hands could no longer grip objects with anything close to full strength. But he was still Jim Brown: sharp as a tack and made of stone.

“I’ve always occupied a special position and been able to get certain opportunities because the system wanted to use my talents for economic gain,” he said to me, “And as long my talents were relevant, I was relevant. But, the greatest desire in my soul was and is to represent myself as a man and carry myself as a man at all times. I wanted to help others and always credit those who helped me. I wasn’t ‘Jim Brown’ always. One time I was 8 years old, 12 years old, 18 years old. So you can’t look at me or anybody as just one block because it doesn’t all wrap up like a big box with candy and ribbons around it and shit. And it isn’t all negative or positive. It just is what it is.”

Something documentarian Ken Burns said makes this understandable to me: “We always lament in the superficial media culture that there are no heroes, but that presupposes that a hero is perfect and what the Greeks have told us for millennia is that a hero isn’t perfect. It’s just the negotiation between a person’s strengths and weaknesses… and sometimes it’s not a negotiation. It’s a war.”

More columns ⇒

Support the Work

Please consider making a donation to keep this site going.

Featured Videos

Dave on Democracy Now!